namrata arjun

(s)praying

20 x 16 inches

Oil on wood panel

(s)praying

20 x 16 inches

Oil on wood panel

(s)praying

16 x 20 inches

Oil on wood panel

figure/ground

36 x 36 inches

Oil on canvas

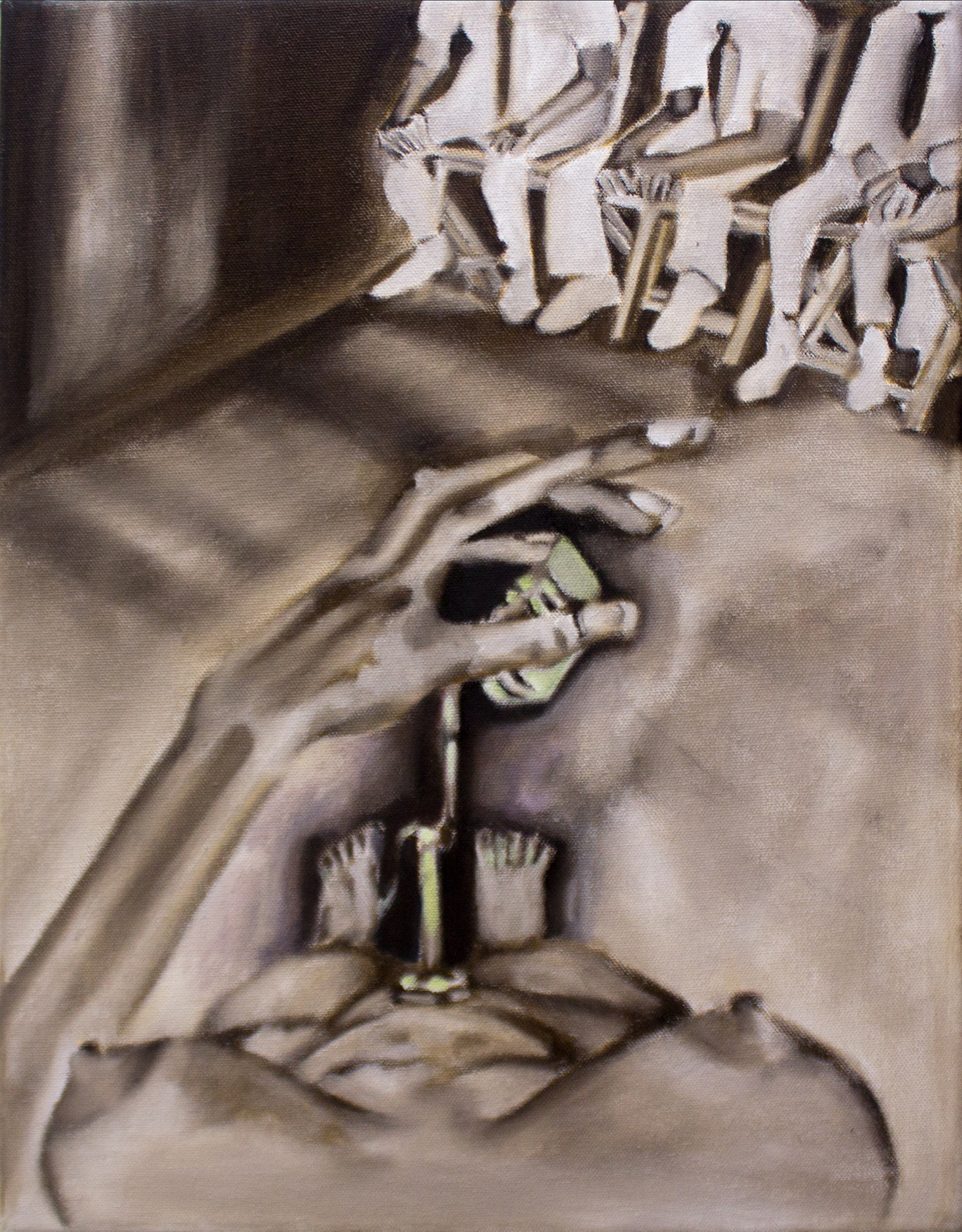

chhinamasta/kill your projections

36 x 36 inches

Oil on canvas

anatomy of a phantom dick

98 x 36 inches

Oil on canvas

ontological striptease

Installation view, Blueprint12, New Delhi, 2022

ontological striptease

Installation view, Blueprint12, New Delhi, 2022

ontological striptease

Installation view, Blueprint12, New Delhi, 2022

ontological striptease

Installation view, Blueprint12, New Delhi, 2022

chhinamasta/kill your projections

36 x 36 inches

Oil on canvas

figure/ground

16 x 12 inches

Oil on canvas

struggle

12 x 10 inches

oil on canvas

(s)praying

16 x 20 inches

Oil on wood panel

pink totes meer

36 x 24 inches

Oil on canvas

anatomy of a phantom dick

18 x 14 inches

Oil on canvas

black square

36 x 24 inches

Oil on canvas

when they are all good, I am all bad

18 x 14 inches

Oil on canvas

when they are all bad, I am all good

18 x 14 inches

Oil on canvas

pentimento

24 x 24 inches

Oil on wood panel

memory / healing the split

24 x 24 inches

Oil on canvas

dis-identification/healing the split

36 x 24 inches

Oil on canvas

drawing holding a photograph

36 x 24 inches

Oil on canvas

Two moments (unsuccessfully) cannibalise each other. I paint the resulting indigestion or uneasy entanglement. One of these moments tends to be imaged by a nude body (which is normatively read as the “female” body), in the first-person perspective, marking the painting’s frame perpendicularly. It interrupts the assumption of a universal subjectivity and refuses to neutrally cater to a detached/objective viewer standing at a certain “visual” distance. Positioned as a personal framing or measuring device, it articulates its ongoing gender-based mis-recognition by enacting a politics of dis-identification, of making strange, and productive dis-inheritance by refusing to assimilate with memories, as “evidenced” by photographs – particularly images from my family’s photographic archive – and by handling personal objects, or re-enacting cultural rituals outside of their permissible contexts such as sacred/classical dance performances. In Queer Phenomenology, Sara Ahmed notes that phenomenology offers a queer angle “by bringing objects to life in their loss of place, in their failure of gathering to keep things in their place” and points to hands as crucial sites of disorientation. In my practice, time and place as performed by images from personal and collective memory (such as the news, mythology, and art history) are conflated, compositionally positioned on a transversal plane, and transformed, through paint, into a re-enactment that the perpendicular body (in first-person perspective) queers by refusing a normative cohesion with. This process re-frames larger issues around representation, by filtering the political through the intimate, familial, bodily and personal. As a compositional strategy, it also blurs the distinction between the centre (embodiment) and periphery (disassociation) of the frame by oscillating between both.

Formulating painterly space into a site for queering time by denoting a warp-weft, rather than linear, relationship with the past through the use of perpendicular and traversal axes, my compositions act as a way to interrupt straight or linear time. Time is rendered, or performed, as non-linear and layered, articulating a queer temporality that invokes the logic of the time of trauma, memory, or excavation. Through the device of nesting time within itself using the differentiated markers of the body in first-person perspective, photographic objects, and gestures from performance traditions, my practice seeks to push back against inherited disappearances.

My use of the body in the first-person point of view, partially inspired by the practices of Joan Semmel and Luchita Hurtado, also seeks to challenge the queer universalism that pervades much of the discourse around gender and sexuality in western academic contexts. According to Madhavi Menon in A History of Desire in India, “In several Indian (mythological, poetic, and religious) traditions, men become women because it elevates (rather than diminishes) them in relation to desire”. I also invoke the trope of erotic love for the divine narrated from the “woman’s” point of view, especially by “male" poets, which is part of literary traditions of the Bhakti and Sufi movements.

In creating processes of translation informed by the logics of memory and painting, particularly somatic, feeling or body-memory, information is layered into an opportunity for disturbing the fixity of the archive, upending its singularity and making it more porous, granular, and elastic.

By re-combining images, drawn from life, photograph, memory, performance traditions and dream re-enactments, the assumed binaries of reality/memory, history/fiction, figure/ ground, or body/architecture are wrenched from their otherwise opposing or mutually exclusive taxonomies. The resulting tension complicates their official status as truth and relativises their various registers as object, performance, fiction and memory. It co- produces a mutant subject position vibrating against its frame, and releases troubled air.

Ambiguous space is created by playing with ideas of the painted surface both enacting ground and seeming upright, marked by the body in intentionally complicated ways. For example, whether it’s standing/lying, swallowed up, angled or set against it in fuzzy or delineated ways. The ground is reconfigured into a perpetually shifting negative or in- between space disoriented by multiple perspectives, and the figure/s alternate between dysphoria and joy.

(un)making liquid memory, oil on hand-cut linen, 36 x 30 inches, 2022

(un)making liquid memory, oil on hand-cut linen, 36 x 30 inches, 2022

(un)making liquid memory, installation view, 2022

UBS Gallery/Bard Exhibition Centre, New York

(un)making liquid memory, installation view, 2022

UBS Gallery/Bard Exhibition Centre, New York

(un)making liquid memory, oil on canvas, 72 x 60 inches, 2022

(un)making liquid memory, oil on canvas, 60 x 50 inches, 2022

(un)making liquid memory, oil on hand-cut linen, 36 x 30 inches, 2022

In creating processes of translation informed by the logic of queering/painting, I seek to transform archival information into an opportunity for disturbing its fixity/singularity (particularly the photographic archive with its colonial history that frame the logics of othering and extraction) making it more porous, producing, rather than re-enacting subject positions.

Investigating the interfacing of queer figuration, paint and historical or intergenerational memory, I seek to position paint as a phantasm, a carrier of psychic space, or as post-humanist techno-science, a technology of the unconscious, or of co-producing a subject position. Aided by the material quality of paint – the fact of it being a pigment, its capacity to evoke the liquid forces of the body interior, colour’s ability to evade objectivity by shifting in response to colour relationships positions it as an an agent of queer world-building and retrieving memory.